In March 2020, as the world was acclimatising itself to the pandemic, David Hockney released an image of bright yellow daffodils titled Do remember they can't cancel the spring. In the midst of such fear and uncertainty it offered a much-needed burst of optimism, reminding us all that nature, with its continuing cycles of rebirth and renewal, could still offer hope.

More like this:

- The climate clues hidden in art history

- Can photography save an Amazon tribe?

- Why living with plants is good for you

Hockney has long appreciated the natural world, both for its aesthetic inspiration and therapeutic qualities: "We can only replenish ourselves by looking at nature," he has said. It is a viewpoint many of us have come to share over the past year as we have taken long walks to calm our racing minds. The results can be tangible; a mere 20 minutes in a natural environment has been proven to lower stress levels. Even looking at images of nature can induce some of the same effects, so it is perhaps no surprise that visitors have been flocking to Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature at The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston while Londoners are eagerly awaiting Hockney's The Arrival of Spring, which opens this week at The Royal Academy.

"People are really loving the show. It's been quite a bad time here with Covid and then the freeze which brought everything to a halt and people's faces just light up when they walk into the galleries," says Ann Dumas, curator of the Houston show, who spoke to BBC Culture in early March, just as Texas was beginning to recover from unseasonably freezing temperatures.

The exhibition, a re-working of the hugely popular 2019 exhibition at The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, explores the two artists' love of nature as well as Van Gogh's unmistakable influence on Hockney. The response to nature for both artists was sparked by a change of scene. When Van Gogh moved to the south of France, he made the colour breakthroughs that led to the vividly coloured still lifes and sun-drenched landscapes that lift the spirits of all who view them, while Hockney's return to Yorkshire after many years in LA gave him a renewed appreciation for the local landscapes that he has depicted in his own uniquely vibrant palette.

Field with Irises near Arles, 1888 – The Houston exhibition explores the two artists' love of nature and Van Gogh's influence on Hockney (Credit: Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

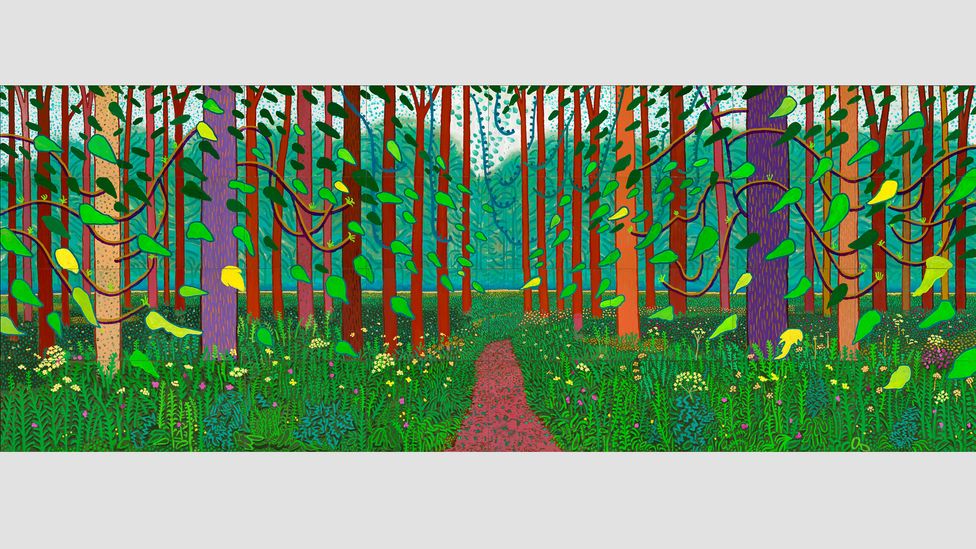

Hockney has said: "I've always found the world quite beautiful, looking at it. Just looking. And that's an important thing I share with Vincent van Gogh: we both really, really enjoy looking at the world." Perhaps unsurprisingly their subject matter frequently overlaps. "We have a beautiful painting by Van Gogh of some tree trunks, but just the bottom part of two tree trunks in woodland in springtime and it's as if he's almost lying on the ground in the wood and in front of him there's this great carpet of wildflowers," says Dumas. Hockney explored the same theme in his monumental The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, 2011 (twenty eleven), in which "everything is really magnified, all the wildflowers are really blown up," says Dumas.

The painting, with its lush, verdant greens and branches tipped with leaves that appear to be writhing and squirming with joy is undoubtedly one of the highlights of the show. As is another work, which Hockney filmed in the same location – The Four Seasons, Woldgate Woods (Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010). Consisting of four panels, each of which are made up of nine subtly moving screens, it shows the same area of woodland as it changes over the seasons. "People are spellbound," says Dumas, "it really pulls you in."

Hockney's The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, 2011 (twenty eleven) is one of the highlights of the Houston show (Credit: David Hockney/photo Richard Schmidt)

The work's soothing vision of winter moving into spring is clearly exactly what Texans were in need of. "People have written to us and said, 'Thank you for bringing us this show,'" says Dumas. "They see it very much as about hope."

A dopamine hit

Hope is certainly what Edith Devaney, curator of the Royal Academy's show, needed in 2020 when she was forced to tear apart the institution's exhibition programme not once, but three times, as the country went into repeated lockdowns. Hockney was in Normandy in France at the time, having always intended to capture the coming of spring there, and began sending through completed works to a select group, of which Devaney considers herself lucky to be one. "I have to say being a recipient of one of those images kept us going," she says. "They're visually delightful and they changed your mood, that's a really interesting thing, the extent to which they are actually mood-enhancing."

She is in no doubt of the impact that bringing the completed series to a wider public will have. "It's one of those rare occasions when an art exhibition will have resonance with absolutely every human being alive. It will mean something to all of us because of what we've been through globally," she says. "It's that idea of the cycle of life, you have to cling on to that… it's a reminder that there is a greater force than ourselves."

Like Dumas, Devaney comments on Hockney's keen observation. In conversation with her in the show catalogue, the artist talks enthusiastically about the variety of greens needed to capture the changing season. His excitement is palpable as he discusses looking out for the first little shoots or waiting to see if his pear or cherry tree will blossom first.

The Royal Academy features David Hockney's latest nature paintings, created using an iPad, such as No 118, 16th March 2020 (Credit: David Hockney)

This excitement and sheer, vivacious joy is apparent in every one of the "iPad paintings", a medium he has made his own over the past decade or so, particularly now he has his own special app devised by a mathematician in the north of England. It allows him, among many other innovations, to slot layers in and out. The paintings convey an excitement that cannot help but be contagious and Devaney believes the show will give visitors who haven't already reacquainted themselves with nature a renewed desire to understand the natural world around them.

"One of the things David's work teaches us to do is look – it's that sort of observation that we lose, we have so many different visual stimuli now, and even more so as we've all been glued to our screens for a year, and this is a reminder that actually that's not proper looking; proper looking is what you do when you're out in nature."

The benefit of really looking, both in terms of creative inspiration and mood enhancement, is something the naturalist, designer-maker and illustrator Emma Mitchell understands well. Mitchell has suffered from depression for many years, and in her book The Wild Remedy she writes beautifully about how immersing herself in nature and creating art and craftworks from her finds has helped her mental health.

"Because I trained as a scientist I'm fascinated by what [nature does] to our minds and brains… even just 10 minutes of daily creativity and a daily walk among trees and plants can make a huge difference to our mental health," she tells BBC Culture.

"If you simply look at images of nature, that could be moving or stills, you get a relaxation response, if you actually go out to walk for 15-20 minutes then levels of the stress hormone cortisol drop significantly… our brains are hard-wired to respond to trees, plants, the sight of leaves and even just the colour green," says Mitchell. The naturally occurring patterns in nature are also likely to improve our mood. "When we see fractals, for example the pattern of branches and twigs is a botanical fractal, you get a similar response in the brain to when we listen to music, which can trigger elation and dopamine," explains Mitchell.

On her walks Mitchell frequently collects natural objects, which she then arranges into sublimely lovely photographs modelled on 19th-Century botanical reference books. Creating the images gives Mitchell herself a dopamine hit, but she also uses her research in the academic sector to ensure that they can offer mental health benefits to her followers when she posts them on Twitter and Instagram. "People really respond positively to gentle colour gradations of either flowers, shells or sometimes leaves in the autumn. It's combining the benefits of seeing an individual plant specimen with the proven effects of fractals," she says.

Artist Emma Mitchell arranges the natural objects that she collects into photos modelled on 19th-Century botanical reference books (Credit: Emma Mitchell)

Audience responses in Texas strongly suggest that images of nature do not have to be scientifically accurate in order to trigger the same responses. "If lots of people are responding positively to that exhibition, and perhaps to certain elements of it, that could be analysed and studied," says Mitchell. "When we simply look at what may be regarded as quite a flamboyant depiction of nature on an iPad, it's quite sweeping and sometimes the colours are unexpected, yet still it chimes with people so strongly that our brain chemistry is likely to be altered," she says.

The Royal Academy's exhibition seems destined to provide the same dopamine hit, but Mitchell says we can all benefit from nature and creativity if we take a leaf out of Hockney, Van Gogh and her own book and get down among the plants to really look. "See if you can encounter something that you think is beautiful, maybe bring a leaf or two home, a feather or a tiny violet, and then commemorate it in some way by pressing it or taking a photograph. That will give you a slight lift, and if you do it the next day it's cumulative. If you keep doing it, it can make a significant difference to your mental health."

Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature at The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston runs until 20 June 2021; David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy 2020 at the Royal Academy of Arts in London runs from 23 May to 26 September 2021.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"bring" - Google News

May 20, 2021 at 06:02AM

https://ift.tt/3fwUH83

Hockney and Van Gogh: How images of nature bring us joy - BBC News

"bring" - Google News

https://ift.tt/38Bquje

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Hockney and Van Gogh: How images of nature bring us joy - BBC News"

Post a Comment